NASA Mars Rover Finds ‘Very, Very Strange Chemistry’ and Ingredients for Life

A trio of new studies using data from NASA's Perseverence rover confirm that Jezero Crater on Mars was once habitable.

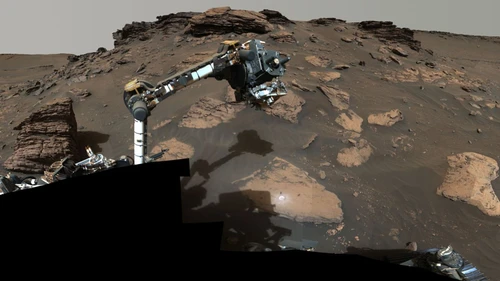

NASA’s Perseverance rover has been searching for signs of life on Mars since it landed in an ancient lakebed on the red planet in February 2021. In a trio of new studies, scientists have revealed tantalizing details about the habitable conditions that once existed on Mars, while constraining the odds of discovering Martian life in the future.

Mars is currently a frigid and desiccated world that is hostile to life, but there is abundant evidence that it was warmer, wetter, and more welcoming many billion of years ago. Simple forms of life may have emerged in the lakes and rivers that once flowed in this ancient era, which is why NASA sent Perseverance to search for fossilized traces of any bygone Martian microbes. The rover is also collecting samples from Jezero Crater that the mission team hopes to pick up with a future spacecraft so that they can be delivered back to Earth for more rigorous examination. The data for the new studies was collected over nearly two years of extraterrestrial exploration.

The teams behind each of Perseverence’s specialized instruments published summaries of their findings in a batch of three studies on Wednesday. The new research follows an August study released in the journal Science that reported a surprising abundance of igneous (or volcanic) rocks in the areas first explored by Perseverance, and offers more granular details about the rover’s new discoveries.

“What's coming out now is the actual instrument documentation of all this evidence that we saw,” said Eva Scheller, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who led the study about SHERLOC, an onboard ultraviolet spectrometer, which was published in Science, in a call with Motherboard. “The way that the rover operates is with different instruments that have different insight.”

“This is actually the first time we have used this kind of instrumentation in a planetary mission,” she added, referring to SHERLOC. “So in itself, it is also a demonstration of a new engineering technique.”

As Scheller and her colleagues describe in their study, SHERLOC detected two distinct periods when the crater was influenced by the presence of water. While it’s challenging to pin down an exact timeline, the team estimated that the area hosted water around 3.8 billion years ago. More than a billion years later, the crater contained a saltier brine that produced “weird” chemicals called perchlorates, Scheller said.

“In that kind of environment, we're seeing very, very strange chemistry which is not common on Earth at all, but seems to be more common on Mars because we've seen these kinds of materials in almost all the missions now,” she explained. “So there are two liquids from different rocks with two different ages with very different chemistry that [SHERLOC] was able to determine.”

The instrument was also able to detect organic molecules, which are key ingredients for life, confirming that habitable conditions did once exist in Jezero Crater.

“There's still ongoing investigation that we're doing,” Scheller said. “But we want to look for organic compounds because we see them as the building blocks for life. They are not necessarily signs of life, but you want to see liquid water and organic compounds together in an environment because they're the key components of what could make an environment habitable.”

The results from SHERLOC help to reconstruct the history of water and organics on Mars, and confirm that Jezero Crater had the right stuff to support microbes, though that doesn’t mean life ever actually arose on the red planet. This general picture was also supported by the other instrument teams.

Besides SHERLOC, Perseverance also carries an X-ray spectrometer called PIXL, and a stereoscopic camera called Mastcam-Z, which has a zoom feature.

The PIXL group detailed their analysis of rocks in the Séítah formation, which showed watery alterations to minerals and crystals that were “previously impossible to unambiguously constrain,” according to a study published in Science Advances.

Meanwhile, the Mastcam-Z team reported that it “found no compelling evidence for lacustrine sedimentation in the crater floor regions thus far explored using the rover,” meaning that the rover has not yet encountered sedimentary rocks that might preserve any ancient signs of life, according to a study that was also published in Science Advances. However, Perseverance has just arrived at the remains of a huge dried-up delta in the crater, which may contain more of this sedimentary rock, which will be detailed in future studies.

Taken together, the new studies advance our understanding of the tantalizing and habitable version of Mars that existed billions of years ago. The mission teams now look forward to many more years of exploration on the Martian surface, and eventually, the successful return of Perseverance’s samples to Earth. Perhaps one day, these efforts might answer one of the ultimate questions in science: Is Earth the only planet that has ever hosted life?

“It's been a really amazing journey,” said Scheller, adding that she began working on this mission when NASA was still figuring out where to land the rover on Mars. “I've really been able to see the mission unfold scientifically from the very beginning, so it's actually a little bit surreal that we finally figured out a place to land and we actually got information from where we landed. It has been a huge undertaking by hundreds and hundreds of people.”

Publication: Eva L. Scheller, et al., Aqueous alteration processes in Jezero crater, Mars−implications for organic geochemistry, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abo520

Original Story Source: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up