Risky Business: Teenage Chimps Risk It All, Like Humans

For young chimpanzees, gambling on the possibility of a big payout is an attractive prospect, whereas adult apes are more likely to hedge their bets, a new University of Michigan study shows.

Young chimpanzees in a sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. Image credit: Alexandra Rosati

Young chimpanzees in a sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. Image credit: Alexandra Rosati

For young chimpanzees, gambling on the possibility of a big payout is an attractive prospect, whereas adult apes are more likely to hedge their bets, a new University of Michigan study shows.

Research on primates can offer insights into the biology of human behavior. Human teenagers grapple with changing bodies and brains, and tend to be more impulsive, more risk-seeking and less able to regulate their emotions than adults.

In this study, which appears in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, researchers examined if chimpanzees deal with these psychological challenges the way that human teens do. Chimpanzees reach adulthood around age 15.

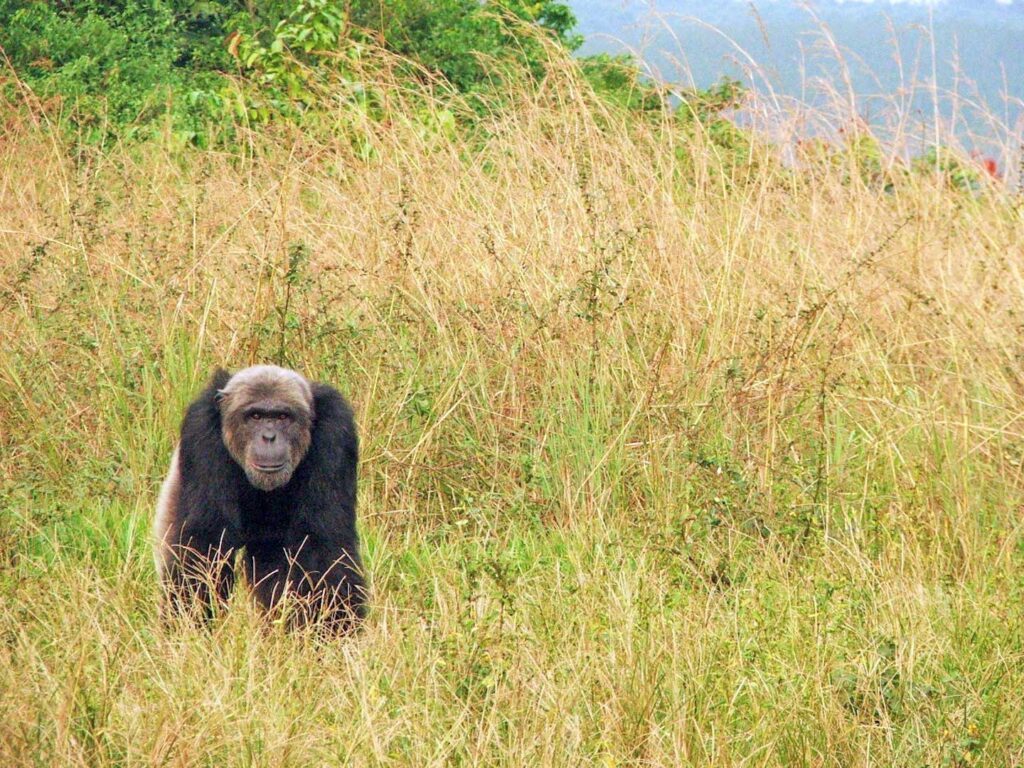

An older chimpanzee in a sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. Image credit: Alexandra Rosati

An older chimpanzee in a sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. Image credit: Alexandra Rosati

“This means they are very similar to us in terms of how they experience a long developmental period, unlike many other animals who grow up much more quickly,” said the study’s lead author, Alexandra Rosati, U-M associate professor of psychology and anthropology.

Researchers examined 40 chimpanzees in a sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. Both young and adult chimps were presented with two games: a ‘gambling’ task where they could either play it safe and get a certain reward or gamble on possibly getting a better payoff; and a delay of gratification task where they could choose between a smaller reward they could have right away, versus a larger reward they had to wait one minute to access.

An chimpanzee in a sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. Image credit: Alexandra Rosati

An chimpanzee in a sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. Image credit: Alexandra Rosati

In both tasks, researchers collected saliva samples to track each individual’s hormone levels, and measured the chimpanzees’ emotional reactions to their choices by tracking if the primates scratched themselves, made an emotional vocalization (similar to a child whining, or threw a tantrum.

While the younger chimps were more risk-prone than adults, they were similarly successful at waiting for delayed rewards. Yet younger chimpanzees were more likely than the older chimpanzees to get emotional while they were waiting for the bigger reward, the research indicates.

“We were surprised to find that younger chimpanzees were just as able to forgo the temptation of immediate rewards and wait for bigger future payoffs as were adults,” Rosati said.

The study’s co-authors were Melissa Emery Thompson, University of New Mexico; Rebeca Atencia, Jane Goodall Institute Congo; and Joshua Buckholtz, Harvard University.

Publication: Alexandra G. Rosati, et al., Distinct Developmental Trajectories for Risky and Impulsive Decision-Making in Chimpanzees, Neuroscience (2023). DOI: 10.1037%2Fxge0001347.

Original Story Source: University of Michigan

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up