New Global Map Of Ant Biodiversity Reveals Areas That May Hide Undiscovered Species

They are hunters, farmers, harvesters, gliders, herders, weavers and carpenters.

An ant (species: Ectatomma tuberculatum) photographed in Costa Rica. Ants make up a large fraction of the total animal biomass in most terrestrial ecosystems, but researchers say that an understanding of their global diversity is lacking. This new study provides a high-resolution map that estimates and visualizes the global diversity of ants. Image credit: Benoit Guénard

An ant (species: Ectatomma tuberculatum) photographed in Costa Rica. Ants make up a large fraction of the total animal biomass in most terrestrial ecosystems, but researchers say that an understanding of their global diversity is lacking. This new study provides a high-resolution map that estimates and visualizes the global diversity of ants. Image credit: Benoit Guénard

They are hunters, farmers, harvesters, gliders, herders, weavers and carpenters. They are ants, and they are a big part of our world, comprising more than 14,000 species and a large fraction of animal biomass in most terrestrial ecosystems.

Like other invertebrates, ants play vital roles in the functioning of ecosystems, from aerating soils and dispersing seeds and nutrients to scavenging and preying on other species.

Yet a global view of their diversity has been lacking.

But an international team of researchers led by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and including a University of Michigan ecologist has developed a high-resolution map that combines existing knowledge with machine learning to estimate and visualize the global diversity of ants.

The team’s findings were published online Aug. 3 in Science Advances.

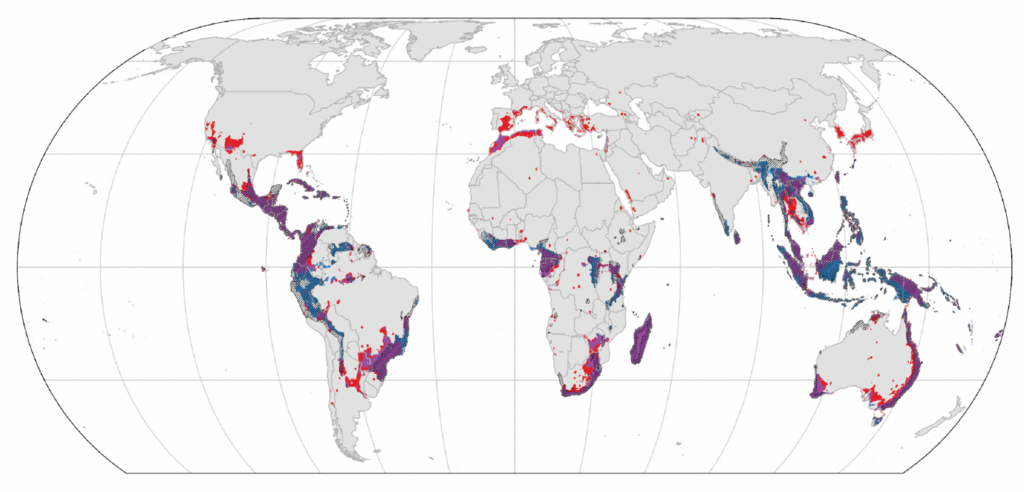

Map highlighting species rarity—the areas with many ant species with very small ranges. The colored areas all indicate important regions for ant species with small ranges. Red indicates areas that are relatively more studied than other areas, which could artificially boost their importance. Purple areas are both important based on current knowledge and are likely to remain so after future sampling. Blue areas are predicted by machine learning to harbor concentrations of undiscovered, small-ranged ant species, giving scientists a treasure map to guide future exploration. This image is an edited version of a figure that appeared in Kass et al., Science Advances, August 2022.

Map highlighting species rarity—the areas with many ant species with very small ranges. The colored areas all indicate important regions for ant species with small ranges. Red indicates areas that are relatively more studied than other areas, which could artificially boost their importance. Purple areas are both important based on current knowledge and are likely to remain so after future sampling. Blue areas are predicted by machine learning to harbor concentrations of undiscovered, small-ranged ant species, giving scientists a treasure map to guide future exploration. This image is an edited version of a figure that appeared in Kass et al., Science Advances, August 2022.

“This study helps to add ants, and terrestrial invertebrates in general, to the discussion on biodiversity conservation,” said Evan Economo of the Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. “We need to know the locations of high diversity centers of invertebrates so that we know the areas that can be the focus of future research and environmental protection.”

The resource will also serve to answer many biological and evolutionary questions, such as how life diversified and how patterns in diversity arose, said Economo, who was a Michigan Fellow at U-M from 2009 to 2012.

“The earliest naturalists recognized broad-scale patterns of biodiversity, but mostly for the vertebrates and plants,” said U-M ecologist and study co-author Nate Sanders. “This impressive collaboration provides the first high-resolution biodiversity map of where ecology’s movers and shakers—the ants—are.”

The decade-long project began when study co-first author and former OIST postdoctoral researcher Benoit Guénard (now at the University of Hong Kong), worked with Economo to create a database from online repositories, museum collections and around 10,000 scientific publications on where different ant species are located.

Researchers around the world contributed and helped identify errors. More than 14,000 species were considered, and they varied dramatically in the amount of data available.

The vast majority of these records, while containing a description of the sampled location, did not have the precise coordinates needed for mapping. To address this, co-author Kenneth Dudley of OIST’s Environmental Informatics Section built a computational workflow to estimate the coordinates from the available data, which also checked all the data for errors.

Along with Dudley and OIST research technician Fumika Azuma, OIST postdoctoral researcher and co-first author Jamie Kass made different range estimates for each species of ant depending on how much data was available. The researchers brought these estimates together to form a global map, divided into a grid of 20-by-20-kilometer squares, that showed an estimate of the number of ant species per square (called the species richness).

The species richness centers identified by the researchers include locations in Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, the tropical Andes, South America’s Guiana Shield, the Atlantic Forest in Brazil, the Mediterranean, several regions in Africa, Madagascar, the Himalayas and northeast India, the Western Ghat Mountains in India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Melanesia and coastal Australia.

In the United States, ant species richness centers are located in Florida, southern California and southeastern Arizona.

The researchers also created a map that shows the number of ant species with very small ranges per square (called the species rarity). In general, species with small ranges are particularly vulnerable to environmental changes.

However, there was another problem to overcome—sampling bias.

The researchers used machine learning to predict what would happen if they sampled all areas around the world equally, and in doing so, identified areas where they estimate many unknown, unsampled species exist.

“This gives us a kind of ‘treasure map,’ which can guide us to where we should explore next and look for new species with restricted ranges,” Economo said.

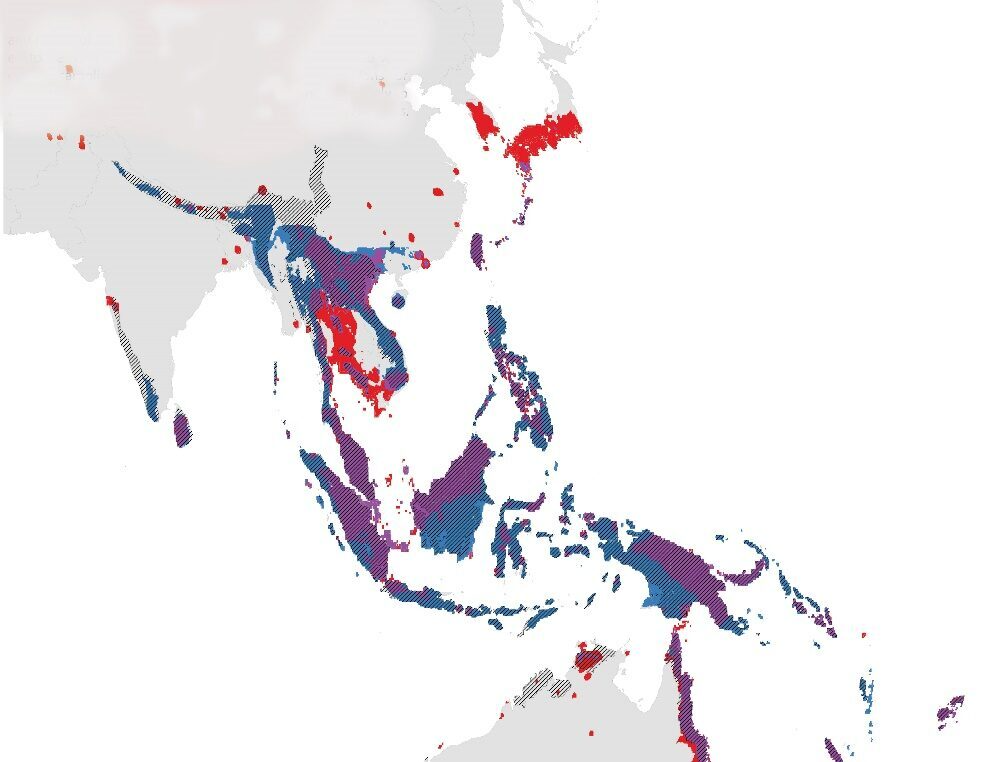

U-M’s Sanders said the southern tropical Andes is “probably the spot where most new ant biodiversity will be discovered. But the Western Ghats in India, much of Southeast Asia, and parts of New Guinea will also likely harbor new and undiscovered ant biodiversity.”

The Atlantic Forest in Brazil, Thailand, Vietnam, many islands in the Philippines and Indonesia, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu are also promising locations, he said.

Map highlighting ant biodiversity centers in Asia—areas that harbor many ant species with small ranges. The different colors indicate how the importance of each region may change with future research around the globe. Red areas are predicted to decrease in importance, purple areas will remain among the most important regions even after more areas are studied, and blue indicates areas that should be targets for exploration as they are predicted to harbor hidden diversity. This is a modified version of a figure in Kass et al, Science Advances, August 2022.

Map highlighting ant biodiversity centers in Asia—areas that harbor many ant species with small ranges. The different colors indicate how the importance of each region may change with future research around the globe. Red areas are predicted to decrease in importance, purple areas will remain among the most important regions even after more areas are studied, and blue indicates areas that should be targets for exploration as they are predicted to harbor hidden diversity. This is a modified version of a figure in Kass et al, Science Advances, August 2022.

When the researchers compared the rarity and richness of ant distributions to the comparatively well-studied amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles, they found that ants were about as different from these vertebrate groups as the vertebrate groups were from each other, which was unexpected given that ants are evolutionarily highly distant from vertebrates.

“This means that focused conservation efforts aimed at protecting a diversity of rare vertebrates might also protect the diversity of rare ant—and other insect—species,” said Sanders, a professor in the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and director of U-M’s E.S. George Reserve.

The researchers looked at how well-protected these areas of high ant diversity are. They found that only a small percentage had some sort of legal protection, such as a national park or reserve.

“The thing I’m most excited about is the treasure map,” Sanders said. “We really need muddy-boots biologists to explore these unexplored places to document the diversity of ants—and other things—before they are lost to habitat destruction or ongoing climate change.”

Publication: Jamie M. Kass, et al., The global distribution of known and undiscovered ant biodiversity, Ecology (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abp9908.

Original Story Source: University of Michigan

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up